Zirl A. Palmer: Pharmacist and Advocate in the African American Community of Lexington

This article first appeared in Pharmacy Chronicles: History of Pharmacy SIG Newsletter.

“Well, the only thing I can say, Labor Day, prior to the bombing, there was a shootout in Berea. This is what the FBI told me. I don’t know. Big man of the Klan in Lexington was killed there, so supposedly the Klan said, ‘We’re going to kill the biggest Black guy in Lexington.’”[i]

[i] Interview with Zirl A. Palmer, August 17, 1978 Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries.

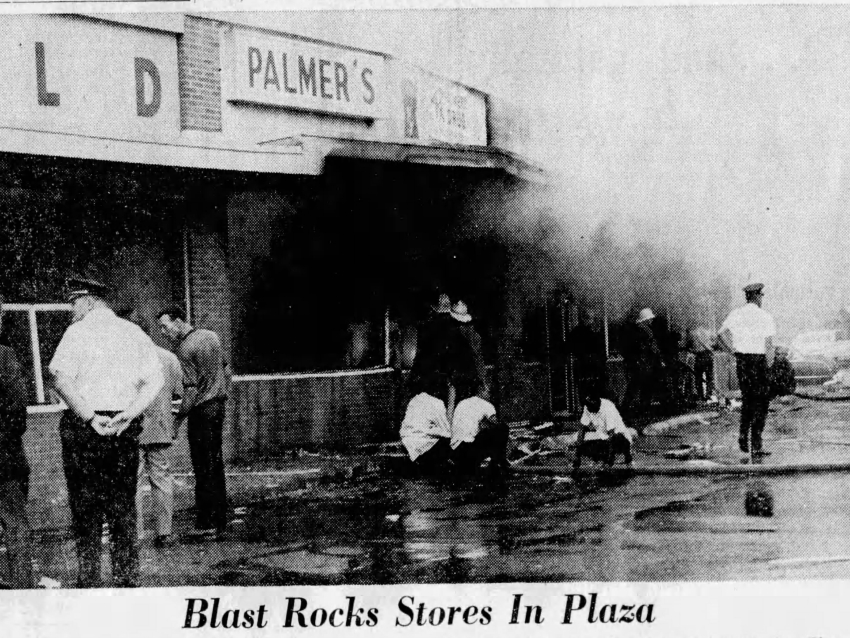

The 1968 shootout was a 10-minute gun battle on the streets of Berea, KY following a rally of the anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-Black National States Rights Party that resulted in the death of two, wounded at least 5 more, and resulted in charges against 14 men.[i] Three days later, Phillip J. Campbell, a former Ku Klux Klan grand dragon, carried out a bombing against Zirl Palmer’s Lexington pharmacy in the West End Plaza, trapping Palmer, his wife, and daughter inside.[ii]

The pharmacy would never reopen, but Zirl Palmer’s legacy as a community leader and civil rights activist was already firmly established. Palmer never set out to become the most prominent Black man in Lexington, but as the city’s lone Black pharmacist in the 1950s, he emerged as a central figure in Lexington’s African American community until his death in 1982.

Early Life and Education

Zirl Augustus Palmer was born December 11, 1919, in Bluefield, WV as the oldest child of James and Lola Allen Palmer. After secondary school, Palmer worked as an inspector’s helper for Norfolk & Western Railroad until the age of 21, when he entered the U.S. Army for three years during World War II (1943-46). Palmer attended Bluefield State College, a local historically black college, where he obtained a BS in Chemistry and Mathematics. He then spent a year at Howard University in the Graduate School of Chemistry, completing courses in the pre-medicine curriculum.

Palmer finished his training in the College of Pharmacy at Xavier University in Louisiana in 1951. While at Xavier, Palmer was an active member of the student body. In addition to his work as a reporter for the university paper, The Xavier Herald, Palmer was instrumental in establishing a student branch of the American Pharmaceutical Association and served as the student group’s inaugural president.[iii]

Patience and Professionalism

Palmer came to Lexington upon graduation in 1951 and opened his pharmacy at the corner of 5th and Race Streets in Lexington’s thriving Black neighborhood of the East End.[iv] Prior to arriving, he knew the city had 9 Black doctors and 4 Black dentists, but no Black pharmacists at the time. His business plan was centered on being the lone Black pharmacist for Lexington’s African American community, and it worked—but not right away.

In Lexington, Palmer’s patience and commitment to professionalism were key. According to Palmer, many people in the African American community had not seen a Black pharmacist and certainly not one as young as Palmer. Despite his training, the community—including some of the local physicians—thought Palmer was too young.1

Without the mentorship of a more senior pharmacist, Palmer maintained his studies, “staying in the books” for the first two years on the job. He abided by the wisdom of the Xavier University Dean of Pharmacy who told him, “Never dispense anything that you actually don’t know what it is yourself.” So he dedicated himself to study to avoid making any mistakes that would undermine his credibility with the local practitioners or his customers. Ultimately, his knowledge, professionalism, and reliable track record garnered the respect of his community, and his business began to prosper.

Innovator and Entrepreneur

While the absence of a designated pharmacist for the African American community drove business to Palmer, his entrepreneurial spirit kept his customers coming back. The pharmacy was a gathering place in the neighborhood and was one of the few places in Lexington where the African American community could sit and drink a soda. When Palmer first opened, he struggled to find a vendor to sell him ice-cream; however, the vendor who ultimately did, Harold Brookings from the Dixie Ice Cream Company, won every sales contest in the Lexington area because of his account with Palmer’s pharmacy. In the first year of business alone, Palmer sold over 5,000 gallons of ice cream. Unsurprisingly, the next year, the rest of the ice cream vendors in the city were also interested in doing business with Palmer.

As a small independent pharmacy, Palmer understood that it was difficult for his store to compete with the major retail chains when it came to the margins on drugs. Instead, the profit was to be made on other items in the store. Ever the entrepreneur, Palmer found innovative ways to draw customers into the store beyond the ice cream and soda that had people lined up out the door. For example, Palmer saw that there were no calendars depicting Black people, so he created his own Palmer’s Pharmacy branded calendars with photographs of the African American community in Lexington. The calendars were very popular, causing community members to approach Palmer as early as September to make sure they could secure next year’s calendar. When his customers looked at their calendar every day, not only did they see images that reflected their community, they also saw the name “Palmer’s.” Palmer understood that representation mattered to his community, a conviction that was evident in his service to the community separate from his business.

Palmer also recognized that no businesses in Lexington were processing utility bills like the pharmacies did in New Orleans where he had completed his pharmacy training. So, he began collecting payment for city utilities inside his pharmacy. All of these things brought customers into the pharmacy and established Palmer’s reputation as a pillar of the East End community.

Following the success of his first pharmacy, Palmer purchased property in 1959 at the intersection of 5th and Chestnut Street. On this location he built a new two-story building to house Palmer’s Pharmacy, Luncheonette, and Doctor’s Office, which opened its doors to the Lexington community in 1961. In this new location, Palmer again demonstrated his entrepreneurship and commitment to the community by combining essential community services in his pharmacy, which housed two physicians and a lawyer in the upstairs suites. Palmer’s Pharmacy, Luncheonette, and Doctor’s Office was the sole Black-owned pharmacy in Lexington at the time and was the first Rexall pharmacy in the United States owned by an African American.

Growth and Loss

The success of the East End pharmacy ultimately led Palmer to open a second, concurrently operating location in the new West End Plaza Shopping Center on Georgetown Street. In the West End Plaza, Palmer’s second pharmacy was adjacent to other businesses, had plenty of parking, and was in a predominantly white neighborhood. In its first year of business, Palmer recalled that the location made three times the revenue his other pharmacy businesses had taken ten years to make. During this time, Palmer continued to be a resource in the Black community for matters of health. As Black doctors in the community passed away, customers would continue to come to Palmer seeking his expertise. He advised on matters where he could and made referrals to other doctors when he could not.

Palmer’s prominence in the community did not go unnoticed. On September 4, 1968—just days after the racially charged gun battle in Berea that killed two men—a man entered Palmer’s West End pharmacy carrying a brown leather briefcase. Palmer and a customer noticed the man and Palmer would later testify that he saw the man leave without the briefcase.[v] The man was Phillip J. Campbell, a former KKK grand dragon, and the briefcase contained a bomb set on a timer made from a cheap alarm clock. When the bomb detonated around 11:20 a.m., Palmer’s pharmacy was in ruins and ten people were left injured. Residents from the nearby Charlotte Court neighborhood rushed to pull survivors from the wreckage.[vi] Buried in the debris of overturned counters and showcases were Palmer’s wife and daughter, who were narrowly saved from the burning building by the heroic men from Charlotte Court.3

Following the bombing, Palmer lived in fear for the safety of his family and made the decision not to reopen the pharmacy. Ultimately, he chose to retire as a business owner, selling the still-functioning East End store shortly thereafter. While no longer a business owner, Palmer continued to serve Lexington as a pharmacist in a local Walgreens and through his service on many state and local councils.

An Indestructible Legacy

Palmer made massive contributions to the health and wellness of the African American community of Lexington as a pharmacist, but his legacy of service to his community was perhaps even greater. Palmer always worked to support and advocate for the Black community as they pursued careers in pharmacy and medicine. He and his wife actively encouraged one of his employees to quit her job working the soda fountain to pursue training as a nurse. Viola Davis Brown would go on to be the first African American admitted to a nursing school in Lexington, and later, the first African American promoted to hospital supervisor at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Lexington.[vii] In addition to creating jobs for clerks and delivery drivers, Palmer employed interns from the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy and wrote recommendations for four of the five Black students he knew had enrolled in Kentucky’s College of Pharmacy as of 1979.

In 1972 Palmer was appointed to a seat on the University of Kentucky Board of Trustees by Governor Wendell Ford and reappointed for a four-year term in 1975 by Governor Julian Carroll. Palmer was not reappointed in 1979 and protests erupted across the state and from the NAACP. As a response, Carroll planned to appoint Palmer to the state Council on Higher Education, a plan that was never completed after the incumbent decided against resigning his post.

Beyond his role as a businessman, Palmer was an active participant in the Lexington community. He played baseball for the Lexington Hustlers—the local professional Negro League team and the first integrated team in the south—and helped coach the University of Kentucky tennis team. He was an active member of Main Street Baptist Church, running a health care program in cooperation with the church. He was active in local branches of Planned Parenthood, the NAACP, the Salvation Army, and the United Negro College Fund, and was the first African American member of the Optimist Club and Big Brothers. He served on the Chamber of Commerce, the Civic Center Board, the Fayette County Board of Health, the Fayette County Recreation Board, and was a member of the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights at the state and local level. Professionally, Palmer maintained his membership with the American Pharmaceutical Association as well as the National Association of Retail Druggists. [viii] Palmer’s vast resume of local and state service underscores his commitment to advocacy and his conviction that African American representation mattered at every level, from city committees to state boards.

Reflecting on Palmer’s business success and community legacy, Ron Griffin, president of the Lexington NAACP, remarked, “It just meant something that a Black person in Lexington could do that. To me, he made a great impact. He’s always been a mover in the community—many times behind the scenes.”[ix] Zirl A. Palmer came to a highly segregated Lexington and made a lasting impact in his communities. From benefitting the personal health of the East End customers that he served out of his pharmacies, to his advocacy for the rights and representation of the African American community, Palmer’s legacy demonstrates the power of the retail druggist to be a community pharmacist in every aspect of the word.

[i] “Berea’s Deadly Racial Shoot-out,” in Matthew Algeo, “All This Marvelous Potential: Robert Kennedy’s 1968 Tour of Appalachia, Chicago Review Press, Chicago: 2020.

[ii] “10 Injured as Bomb Rocks West End Shopping Plaza; Arson Investigation Set,” Jim Ennis, Lexington Herald, September 5, 1968.

[iii] “Pharmacists Receive Special APhA Charter at Special Assembly” by William D. Simon, Jr., The Xavier Herald, April 1, 1951.

[iv] Race Street was historically linked to Lexington’s thoroughbred racing industry, running adjacent to the one-mile dirt racetrack of the Kentucky Association.

[v] “Drug Store Bombing Trial Under Way,” The Lexington Herald, July 7, 1970.

[vi] Keith O’Brien, Outside Shot: Big Dreams, Hard Times, and One County’s Quest for Basketball Greatness, St. Martin’s Press: New York, 2014.

[vii] “Brown, Viola Davis,” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, accessed February 10, 2023, https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/798.

[viii] “Zirl A. Palmer” pp 393-94 by John A. Hardin in The Kentucky African American Encyclopedia, edited by Gerald L. Smith, et al., University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

[ix] “Zirl Palmer, First Black UK Trust Dies at 62,” Lexington Herald, May 21, 1982.